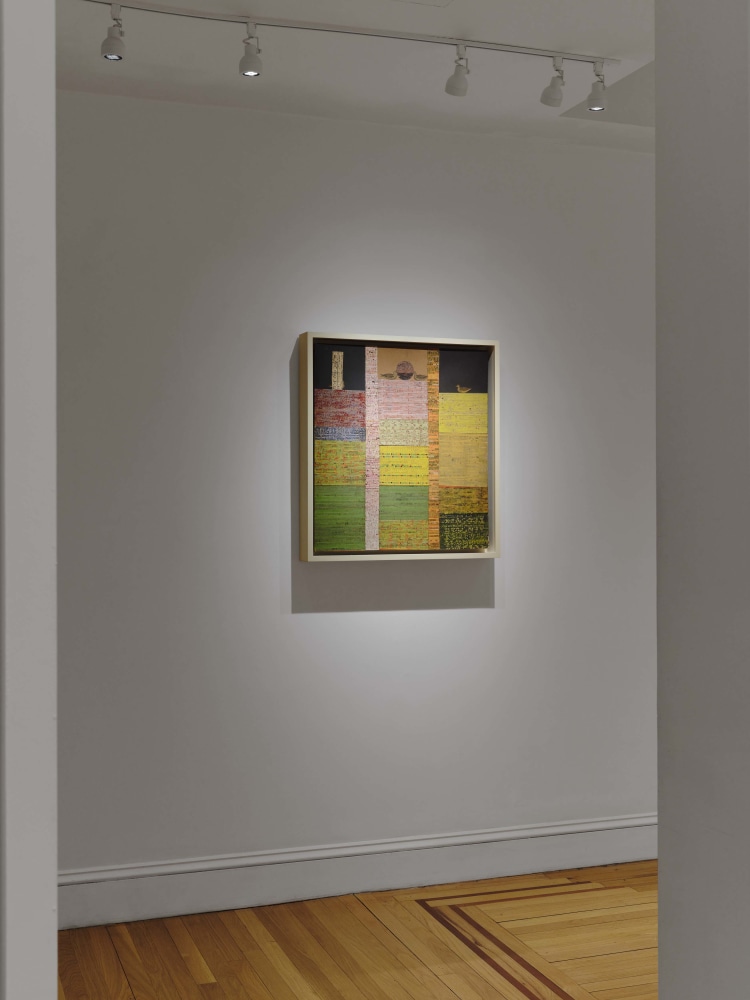

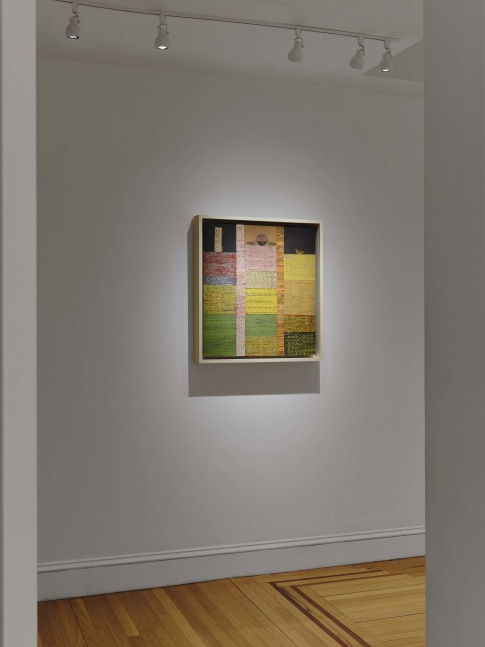

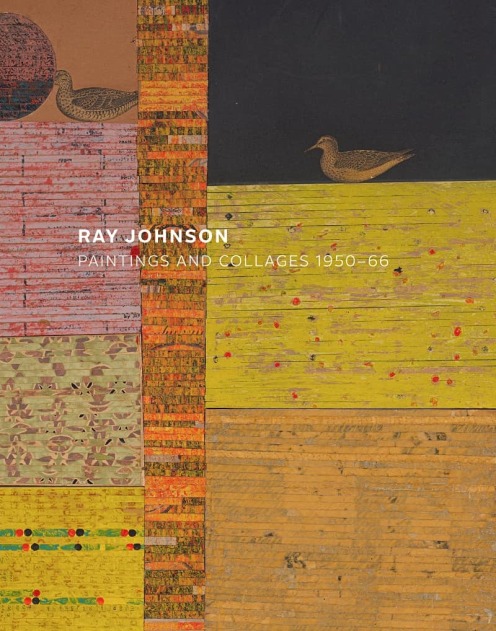

NEW YORK – Craig Starr Gallery is pleased to present Ray Johnson: Paintings and Collages 1950-66, on view from March 28 through June 29, 2024.

This exhibition brings together a selection of Ray Johnson’s rarely seen abstract paintings, along with his intricate, pasted-paper collages, and “moticos.” The show maps the various practices Johnson pursued in the early part of his career, and demonstrates, in the words of scholar Johanna Gosse, “that painting and collage were not separate phases in Johnson’s oeuvre but rather coterminous practices, or, to use the artist’s preferred term, they were in correspondence.”

In the late 1950s, Ray Johnson destroyed most of his early work: paintings, some collages, even his class notes from Black Mountain College, the experimental liberal arts school outside Asheville, North Carolina, which he attended in the 1940s. The abstract paintings in the exhibition are among the few that survived this ritualistic purge, spared because they were previously gifted to close friends and romantic partners.

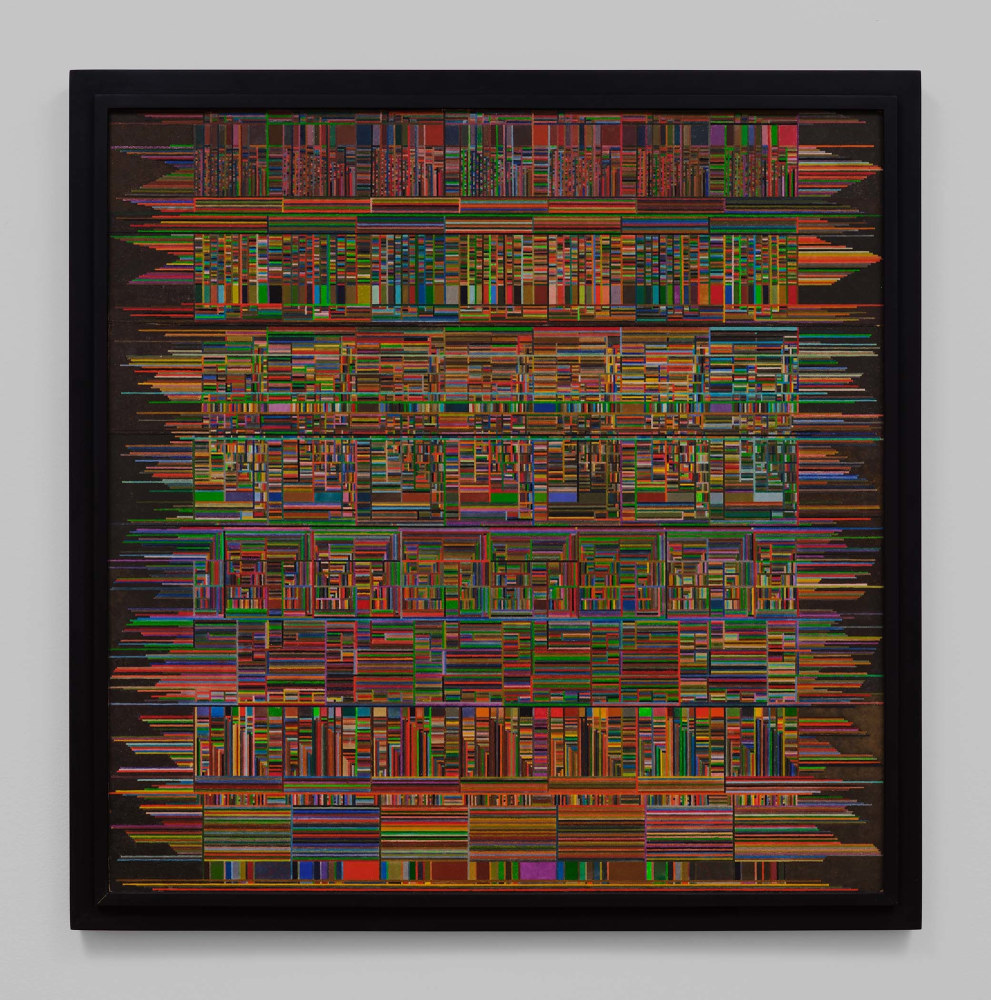

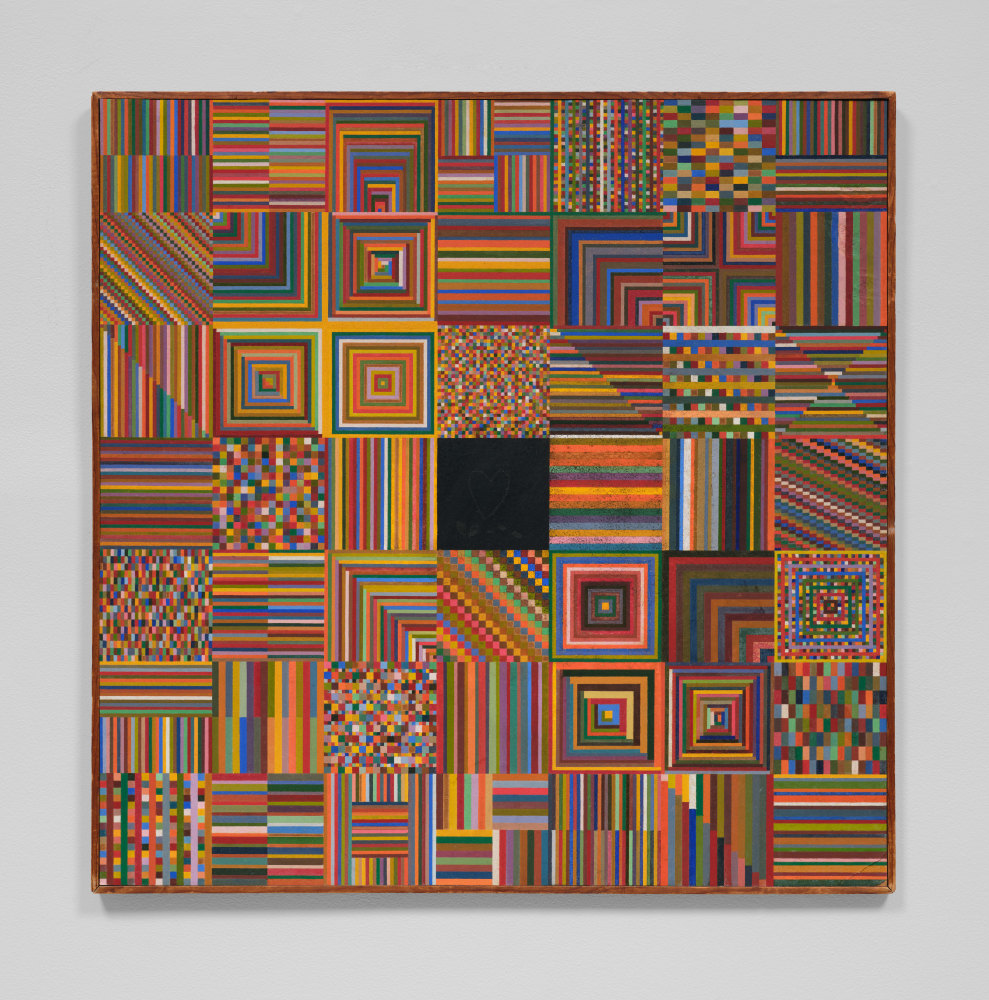

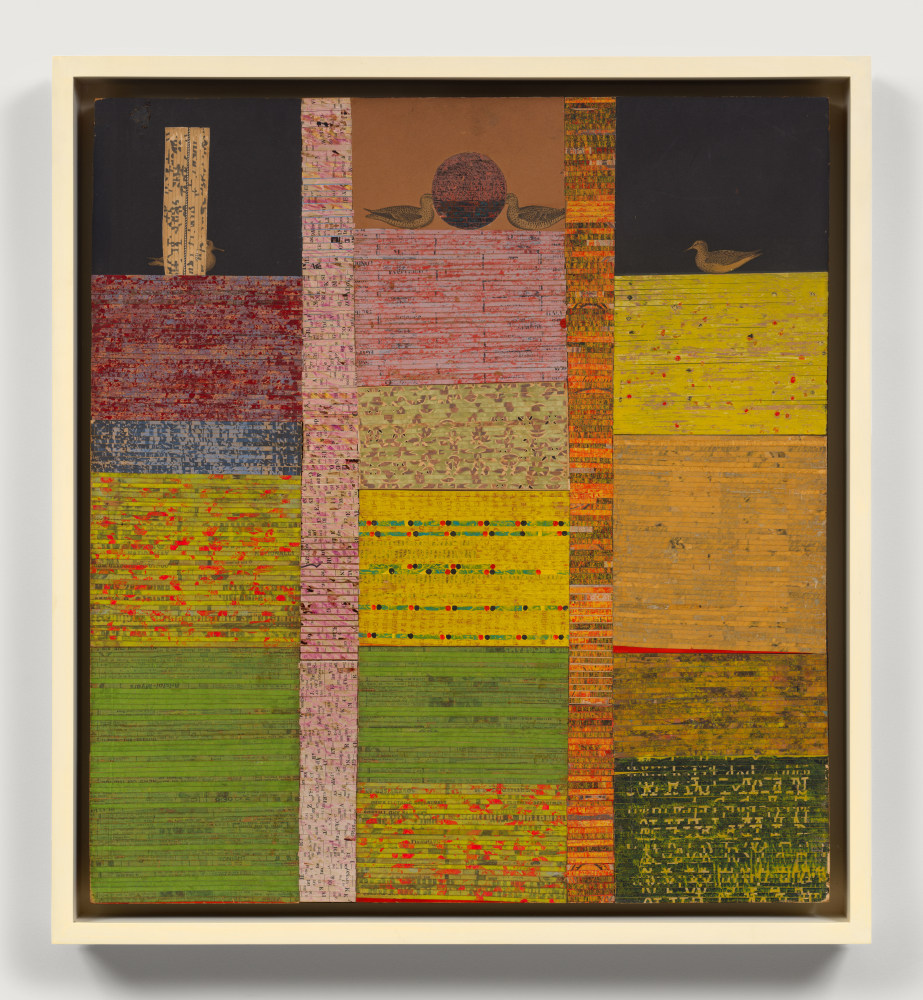

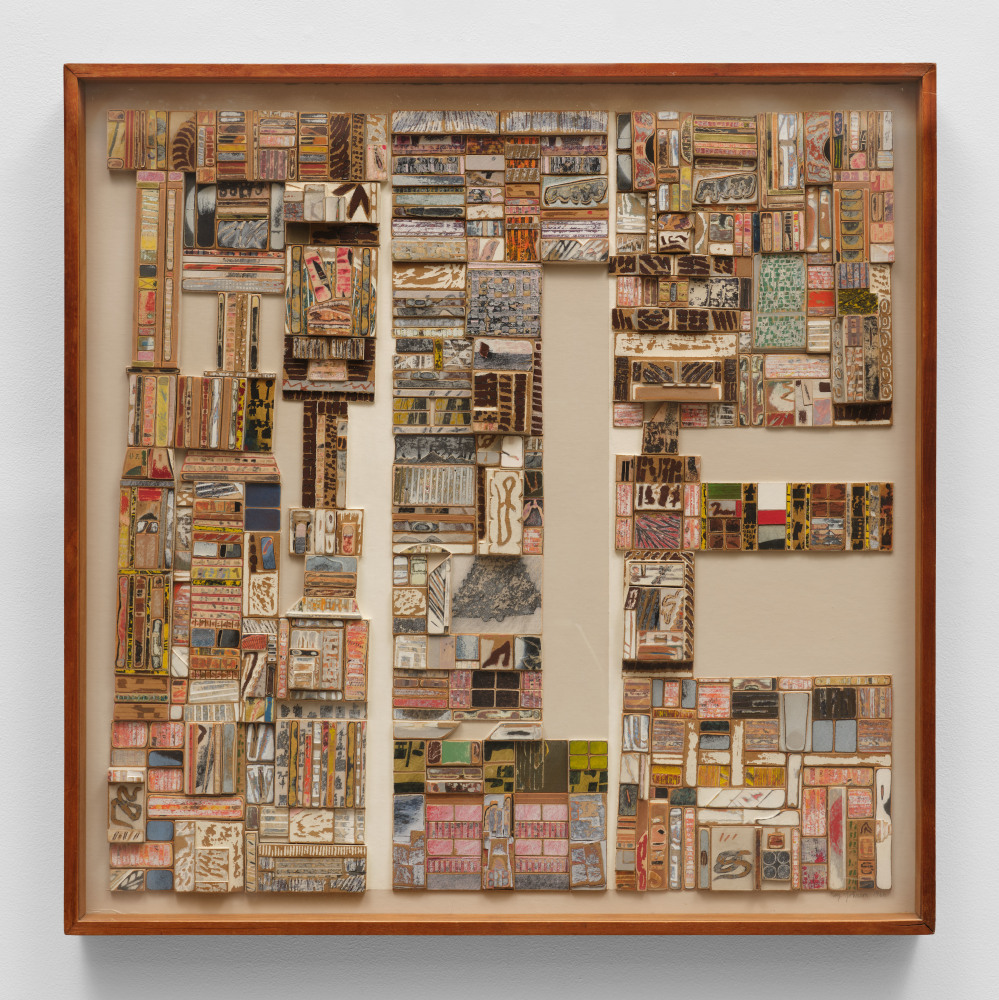

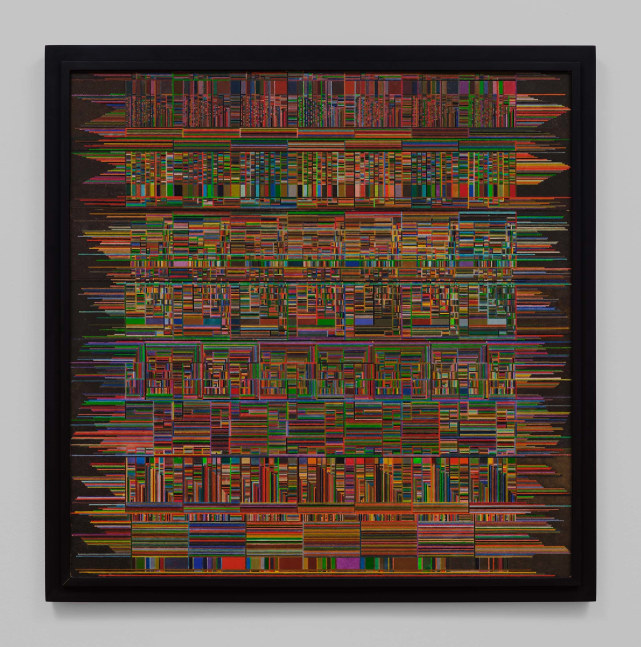

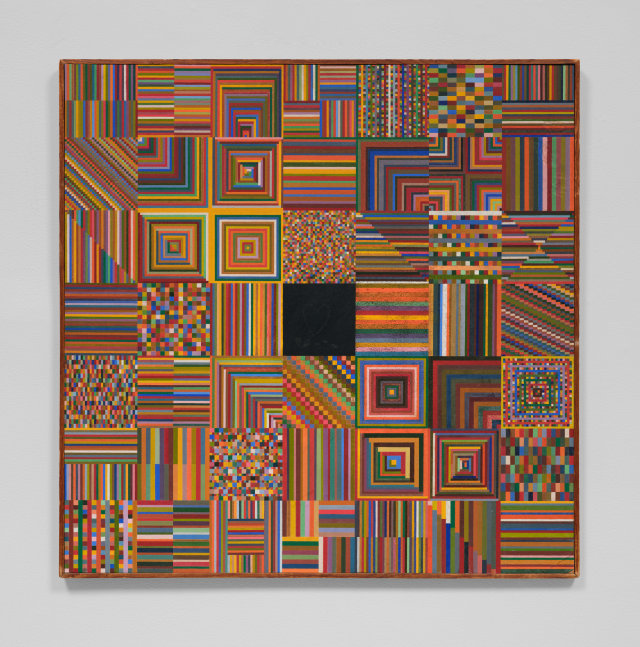

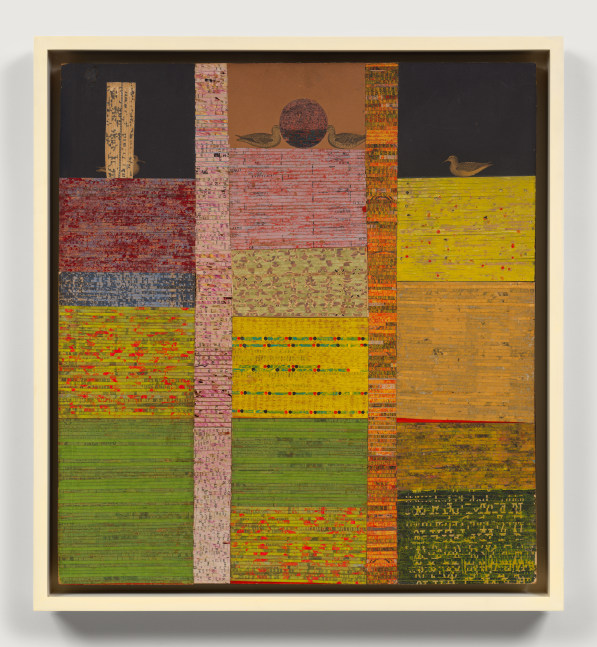

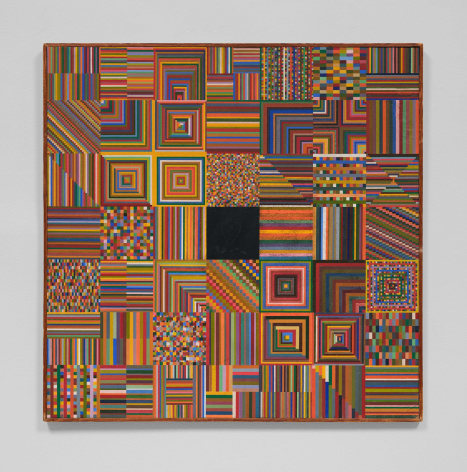

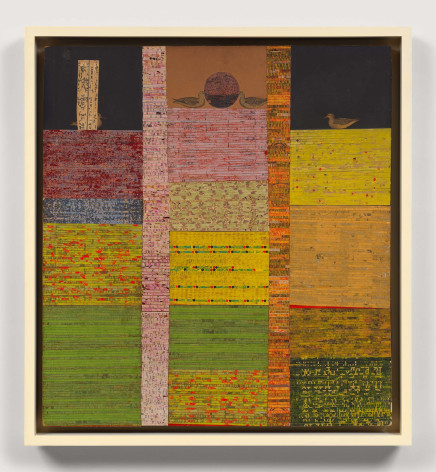

Some of Johnson’s paintings and collages showcase his preference for dramatically contrasting colors and repetitive geometries. Almost ten years apart, the painting, Calm Center (c. 1949-55), and the collage, Birds (c. 1960), are both vibrantly colorful, tapestry-like compositions made up of self-contained, individual squares or grids. In Calm Center, each square has a unique geometric design, an autonomous system, ranging from mosaic tiles to stripes to concentric squares. Birds is organized in contrast by the color of the pasted elements carefully arranged in an all-over grid with a more unified design. Calm Center, a painting given to Richard Lippold, a sculptor and longtime lover of Johnson, is a key transitional piece, as Johnson returned to it in 1955 to inscribe a heart at its center. This heart foreshadows the imagery in Johnson’s collages, like Birds, a move away from the methods of abstract painting towards a collage practice that incorporates language, signs, and recycled materials from the outside world.

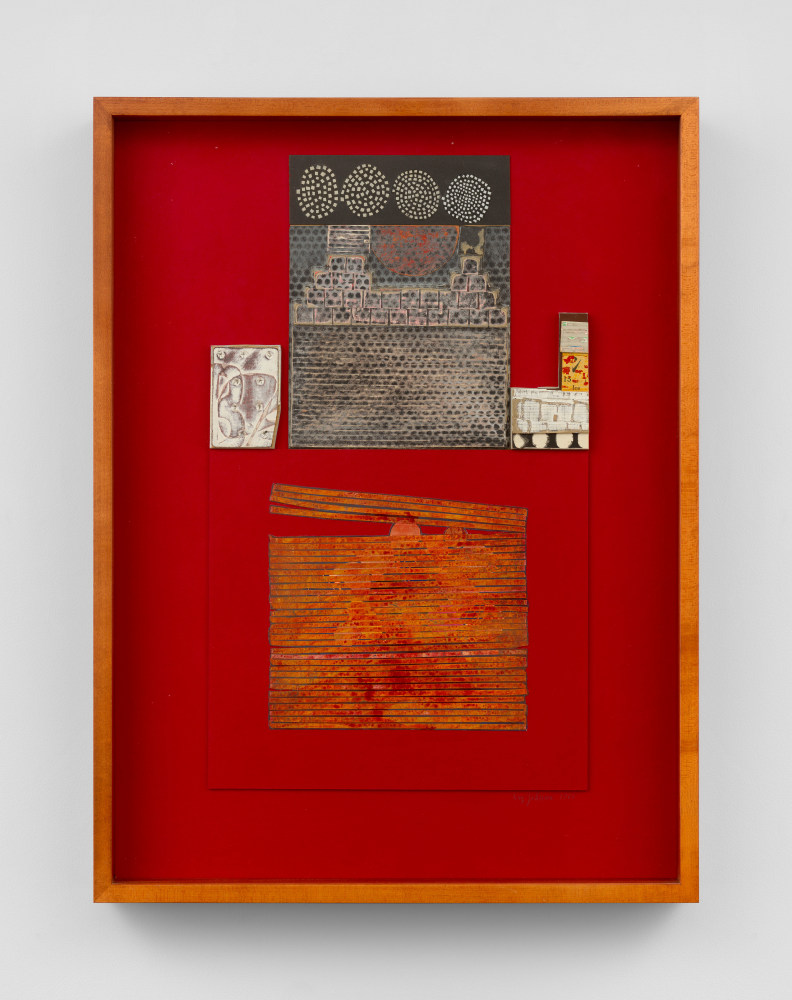

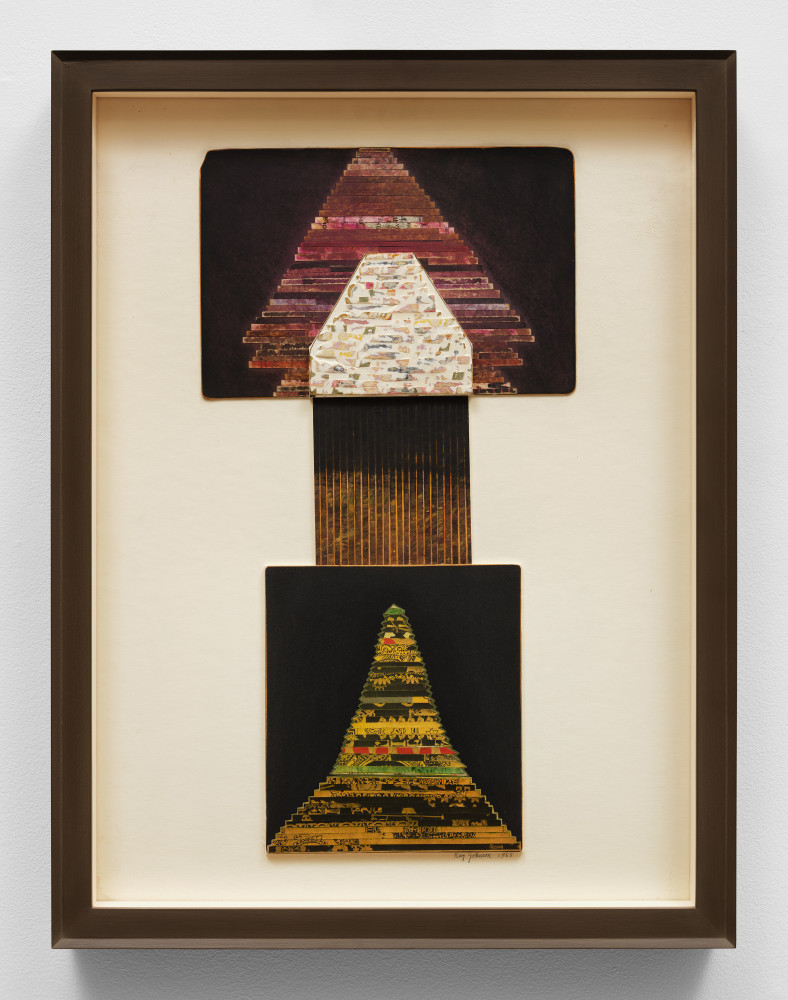

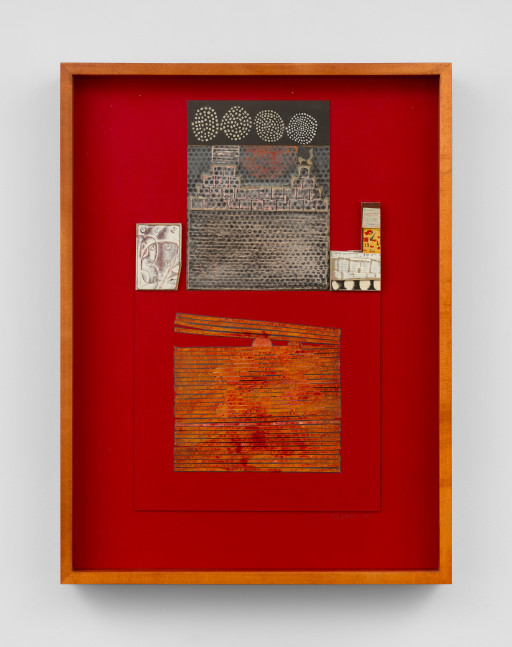

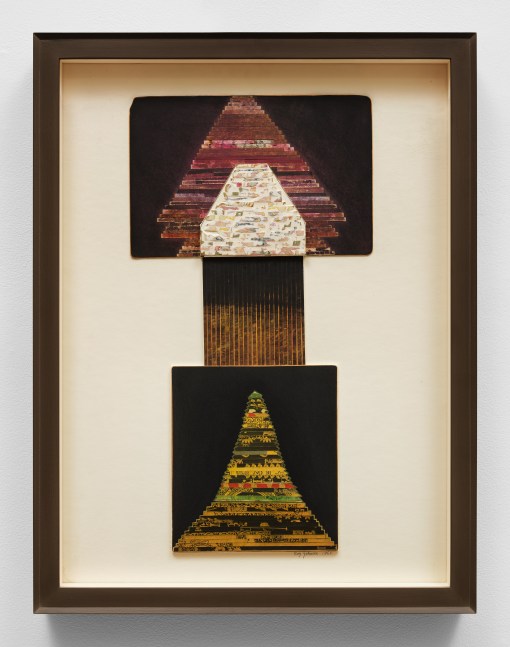

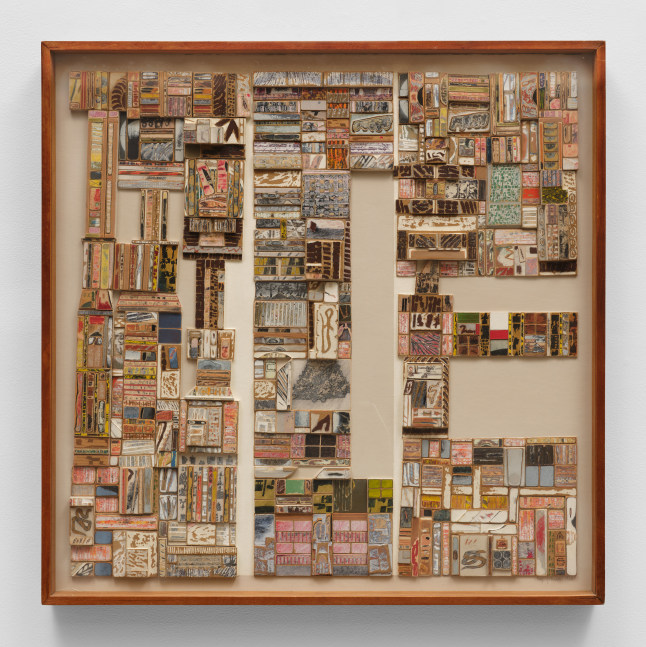

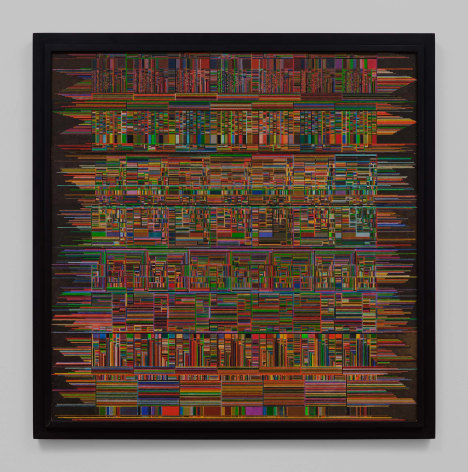

After the destruction of his early work, Johnson reworked some of his collages into symbolic configurations, that he often called “moticos.” In pieces like Totem (1965) or ICE (1966), Johnson cut and pasted strips of colored and printed material, including elements from previous works, to suggest the shape of a “totem” or spell the word “ice,” the pictures’ titles. As opposed to Birds, where the images of birds accompany an otherwise abstract composition, the “moticos” are constructed as glyphs, letters, or signs. Similarly, Comb shows two painted images of combs, seemingly stenciled shadows, suggestive of persons within a house-like structure. The combs also refer to Marcel Duchamp’s readymade Comb (1916; Philadelphia Museum of Art), an everyday object that fascinated Johnson as a transcendental symbol. In a letter to Lippold, Johnson wrote, “I’d like to write an illustrated treatise on the comb in art from Paleolithic times to Picabia, Arman and Johnson-Duchamp.”

A fully illustrated catalogue accompanies the exhibition and includes a new essay by Johanna Gosse, writer, art historian, and lecturer at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She is also currently the Terra Foundation for American Art Visiting Professor in the Department of History of Art at the University of Oxford.